The Paradox of Expertise

In medicine, experience counts. It sharpens intuition, improves efficiency, and helps us recognise patterns that novices miss entirely. Yet the very qualities that make experience valuable can also make it dangerous.

The more familiar we become with certain presentations, the less closely we examine them. Cognitive shortcuts develop out of necessity—our brains are wired to reduce effort by compressing information. Over time, efficiency becomes a point of pride. We know what a “sick” patient looks like. We know which stories usually lead nowhere. We know which rituals “just work.”

Until they don’t.

Expertise, when left unexamined, quietly shifts from a strength into a set of rigid assumptions. We start seeing what we expect rather than what is in front of us.

Why Cognitive Bias Targets the Experienced

We tend to assume bias affects inexperienced clinicians more than seasoned ones. In reality, experience simply gives bias more material to work with.

Years of being mostly right can build a sense of certainty that is difficult to challenge. The overconfidence effect creeps in. Decisions are made faster, with fewer questions. Anchoring becomes more seductive: once we’ve named a diagnosis early, it takes a lot to dislodge it. Confirmation bias steps in to help maintain the illusion that we were right from the beginning.

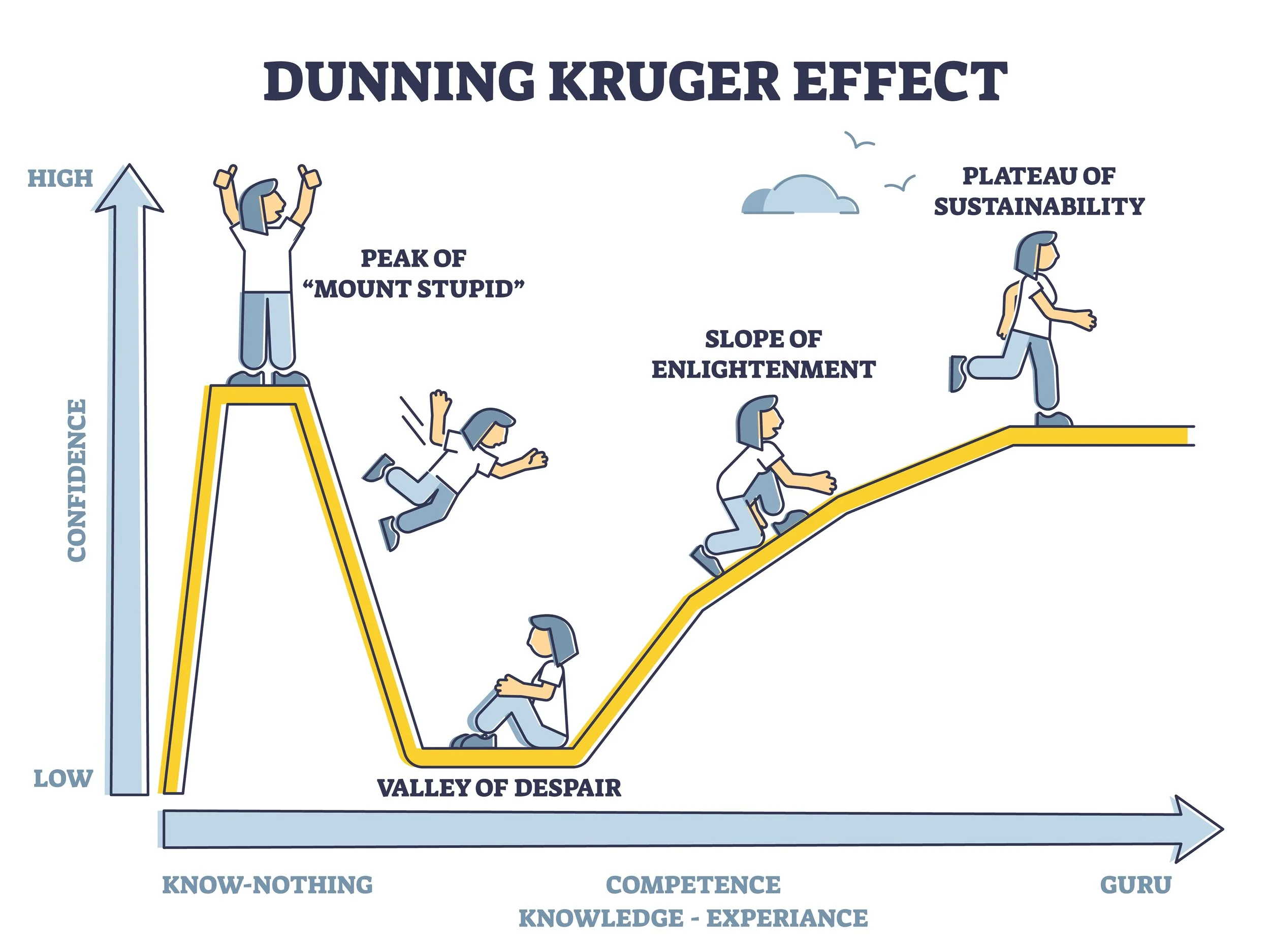

Even the famous Dunning–Kruger curve has a second rise—after the valley of humility comes a gradual return to confidence. For experienced clinicians, this confidence can crystalise into an identity: “I know what I’m doing.” And we do—most of the time. The trouble comes from the times we don’t.

Bias doesn’t disappear with experience. It adapts to it.

When Old Maps No Longer Match the Territory

Examples of experience turning into habit are everywhere in modern medicine.

Take pain management. Many clinicians trained during an era when opioid prescriptions were almost reflexive. The culture has shifted dramatically; multimodal strategies are now preferred and opioids de-emphasised. Yet some habits persist because they were learned during years of clinical apprenticeship when opioids were considered almost universally appropriate.

Well practiced rituals linger. Routine oxygen for MI. Unnecessary pre-op tests. “Must-have” post-procedure imaging. These practices survive not because they withstand scrutiny but because they were once entirely reasonable—and experience turned them into reflexes.

Technology exposes the same pattern. I’ve seen clinicians dismiss handheld ultrasound, risk calculators and EMR prompts simply because they didn’t exist when they were trained. Tools outside our formative years often feel unnecessary, even suspicious.

Experience is powerful. But what we learn early, we defend fiercely.

Why Experience Tricks Us

Experience offers something intoxicating: speed. When we’ve seen a condition dozens of times, we glide through the assessment. We know the questions, the red flags, the usual trajectory. This feels like mastery.

But speed can hide errors.

Repetition makes our brains efficient but also lazy. We begin to rely on memory rather than curiosity. Emotional memories—like that one catastrophic deterioration years ago—loom disproportionately large and distort risk perception. The rare event becomes the rule. The common-but-subtle presentation becomes invisible.

One of the most seductive traps is the “in my hands” fallacy: the belief that personal experience outweighs population-level data (you may be right, but how would you know?). We remember what worked for us—not necessarily what works reliably across the system.

Experience doesn’t usually lead us astray deliberately. It just quietly shapes our thinking without our awareness.

The Cost of Unexamined Expertise

When we rely too heavily on experience, the costs ripple outwards.

At the bedside, outdated habits delay diagnoses or create blind spots. A patient with an unusual presentation may get filtered through a mental template that no longer fits.

Within teams, a senior’s certainty can shut down the instincts of juniors—the very instincts that might catch what we miss. When seniors unintentionally model unexamined certainty, juniors inherit those shortcuts as truth.

And in training environments, these unchallenged habits become culture. Ritual replaces reasoning. “This is how we do things” becomes a defence rather than a question.

None of this stems from malice or incompetence. It stems from a very human tendency: to trust what has worked before.

Debugging the Clinical Mind

But there is a way forward. Experienced clinicians can recalibrate by deliberately “debugging” their mental models.

This means taking moments—after unexpected cases, during debriefs, in quiet reflection—to question why we thought what we thought. It means seeking out data that challenges our assumptions rather than confirms them. It means slowing down in cases that feel too familiar, precisely because familiarity is the risk.

True expertise is not rigid. It is fluid, curious, and willing to break its own habits.

CPD as a Mechanism for Recalibration

CPD is often framed as compliance, but in its purest sense it is the antidote to cognitive drift. Regularly updating evidence, reviewing unexpected outcomes, discussing cases with peers, auditing practice patterns—these are not bureaucratic hoops but mechanisms for keeping our mental models aligned with reality.

When used well, CPD protects us from the illusion of mastery.

It invites us to re-examine what we think we know.

Conclusion

Mastery in medicine is a moving target. It is not an endpoint but a posture. The safest clinicians are not the ones with the most years behind them, but the ones who remain teachable despite those years.

Experience is a gift. But only if we keep sharpening it.

The danger is not in experience itself—but in believing it is complete.